The big news in tech today is that the European Union (EU) has reached agreement on its “Digital Markets Act” (DMA) which aims to “make the digital sector fairer and more competitive”.

Like the EU GDPR, DMA will have far-reaching impacts, especially on the world’s biggest tech companies: Google, Apple, Amazon, Meta (Facebook), etc. At least that will be the case in the EU – Canadians are unlikely to be directly affected, although some of the new DMA regulations may have repercussions outside of Europe (more on that at the end).

To get started, let’s look at some of the biggest changes DMA is bringing to technology in Europe.

EU is coming for Big Tech

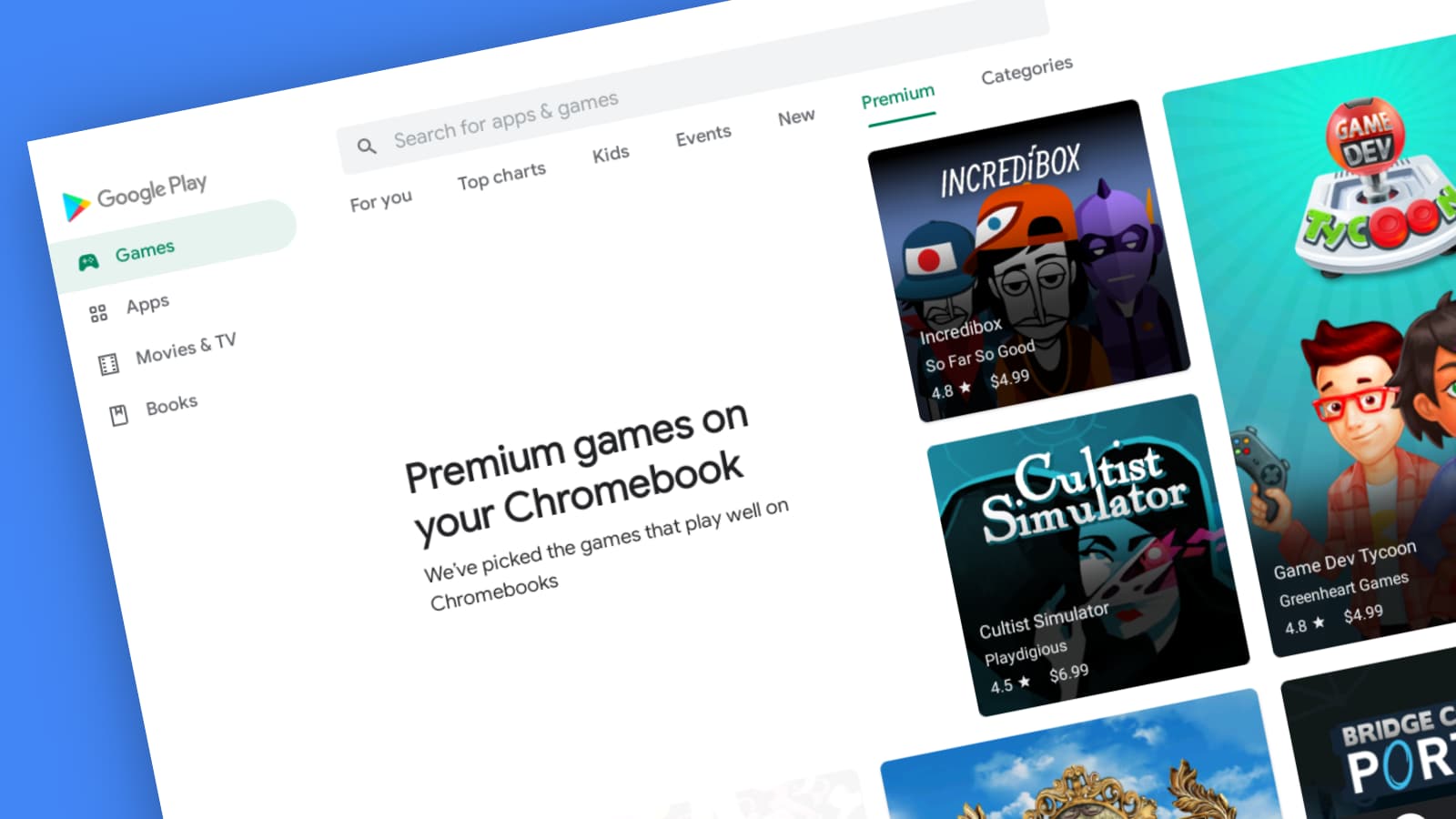

The DMA is set up to target what the EU calls “gatekeepers”, defined as companies controlling one or more core platform services in at least three EU member states. The smartphone app stores of Google and Apple are excellent examples of this, as they are basic services available in several European countries. However, services such as search engines, social networks, cloud services, advertising, voice assistants, web browsers, etc. also fall into this category.

In addition to the focus on access control, DMA has certain revenue, rating, and active user thresholds that companies must meet before the regulations take effect. These requirements mean that the DMA applies almost exclusively to large tech companies like the ones mentioned above.

The DMA also outlines penalties for companies that don’t follow the rules. The legislation provides for fines of up to 10% of a company’s worldwide turnover and up to 20% for repeat offenders. Companies that fail to comply at least three times in eight years can be subject to a market investigation by the European Commission and, “if necessary”, the commission could break up these companies or prevent them from carrying out new purchases.

Rules target data sharing and default applications

Some of the new DMA rules are quite simple. For example, the DMA now requires companies to allow users to use only specific parts of their services with the ability to opt out of other parts. android font suggest using YouTube but not Gmail or Android as an example.

Additionally, under DMA, companies must explicitly ask users for permission to use their data on different services.

Perhaps one of the most important requirements of DMA is that base software can no longer be the default when installing an operating system. For example, it would mean no more default web browsers – a blow to Google’s Chrome and Microsoft’s Edge.

That said, it’s worth noting that the EU has already forced Google to unbundle Chrome and Search on Android devices sold in the EU. Instead, users can choose their preferred browser and search engine during setup. I’m interested to see how this particular rule will apply to things like Chrome OS, where the OS and the browser are effectively the same thing.

However, this rule also applies to hardware. For example, DMA requires developers to be able to access additional smartphone features like NFC chips. It’s a blow for Apple, which only allows its payment services to work with the iPhone’s NFC chip. Under DMA, the chip would become accessible to third-party payment services.

Message interoperability is a nice, but annoying addition

One of the most important additions of the DMA is the requirement for companies to “guarantee the interoperability of the basic functionalities of their instant messaging services”.

In other words, messaging services should open up their platforms to enable cross-service messaging. On the one hand, it seems to solve the frustrating problem of trying to get all your friends to use the same messaging service. On the other hand, it would probably be a total nightmare to implement.

Right off the top of my head, that would mean opening up iMessage, WhatsApp (and various other chat apps from Meta), Telegram, Signal, Google’s RCS system, and Hangouts, and many more, to somehow work. each other (although some of the smaller services may be exempt from DMA). It’s not impossible – WhatsApp and Signal, for example, rely on the same method to encrypt messages and could therefore theoretically be interoperable. Meta is also working to link all of its chat apps so that WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook users can all receive messages in one place.

Besides the technical complexity of creating interoperable messaging, there’s the question of whether developers would even want it. For example, Signal prides itself on its encryption and security – the app is often used as a messaging tool allowing journalists to securely contact their sources. But if it were to become interoperable under the DMA, it could pose a risk to the encryption and trust that Signal has built over the years if suddenly these messages are linked to a system also used by Meta and Google.

Assuming message interoperability is well implemented with strong encryptions and consumer protections, I could see that a unified system is generally a net positive. But I have my doubts about what we will get.

Will AMD have an impact on Canadians?

The short answer is probably no, although like everything, it’s complicated. My best guess is that the AMD will not directly impact Canadians, although some of the broader requirements of the new regulations may have ripple effects.

I think it really depends on the depth of the changes to be made. Things like new default app requirements are unlikely to go beyond Europe, judging by how Google handled its previous unbundling of Chrome and Android in the EU.

At the same time, I think requirements such as messaging interoperability could extend beyond the EU given the technical complexity of implementing such a solution. If businesses need to do all the hard work to make messaging platforms work together in the EU, why not expand that capability to other countries too?

Finally, as noted The edge, the DMA has not passed yet. The EU still needs to finalize the language of the legislation before it is approved by Parliament and Council. However, the DMA could go into effect in October, so it’s not that far off. If and when the DMA passes, I expect some companies to challenge it. In addition, the EU will probably give companies time to comply with the obligations of the legislation.

It will be interesting to see how this all pans out and, if DMA is successful, it could pave the way for restrictions on big tech in other countries as well.

Header image credit: Shutterstock

Source: Android Police, The Verge